Reasoning in AI (2025)

From “think step by step” to thinking as a first-class system primitive.

For a long time, reasoning in language models felt like a discovery. “let’s think step by step” — and the model would suddenly appear more competent. Better at following logic, improved math and coding skills, and less likely to hallucinate. It gave transparency in its inner dialogue. The improvement felt real, but also fragile, like you were peering into a system that didn’t quite understand what it was doing.

2025 changed

Reasoning stopped being something we asked models to do and became something they did by default. New models no longer wait for permission to think. They arrive already equipped with internal workflows that expand, branch, verify, and sometimes even backtrack before producing an answer.

This shift didn’t come from better prompts. It came from changing what we optimized.

2. Agentic tool calls -> same as reasoning. Reward for formatting and correctness of tool usage.

3. reduced hallucinations -> RL + Tool use. Penalize for producing transient facts and let it use tool to get accurate data (e.g. web search). This way model weights forget certain type of facts during post-training that it acquired in pre-training.

4. improved coding -> RLVR to let it discover coding abilities with experience.

While in 2024 many people held reservations in LLM's ability to be accurate and trustworthy, dismissing it as "autocomplete" or "next-token predictor" which compounds errors, they missed thinking from first principles around the technology. We could extend the same ideas to improve: Intelligence, Contextual awareness, Correctness.

Compression of knowledge, which all LLMs and diffusion models are, builds intelligence by identifying and preserving meta-patterns. Cross-attention and long context attention techniques allows it to selectively think over entire context before outputting even a single token. RL allows multi-step optimization towards a meaningful domain-specific objective beyond "produce a helpful, human-like text".

That seems like a lot in 2025, but how did we get here?

From prompting to training to 'think'

The modern story of reasoning often begins with “Large Language Models Are Zero-Shot Reasoners.” The paper’s key insight was almost embarrassingly simple: append “let’s think step by step” to a prompt, and performance improves. What looked like a prompt hack was actually something deeper — the model had latent reasoning behaviors that could be unlocked with the right cue.

Researchers quickly realized that if a model could reason when prompted, it could also be trained to reason without prompting. The question became: how do you make reasoning the default rather than the exception?

The answer turned out not to be architectural. It was objective-level.

When you fine-tune a pretrained LLM using reinforcement learning and reward it only for correct outcomes, something interesting happens. The model learns that short, impulsive responses are risky. Longer internal deliberation correlates with higher reward. Over time, the policy shifts. The model starts to “think” before it speaks.

This is the core idea behind the first modern thinking models.

Many reasoning tasks have high computational depth even when the final answer is simple. Attempting to map input directly to output compresses a long computation into a single step, which dramatically increases variance — both for humans guessing mentally and for models sampling from a distribution. Breaking a problem into intermediate states externalizes computation, increasing time but reducing the effective search space at each step.

In learning terms, it reduces variance at the cost of additional compute. Each intermediate step conditions the next, shrinking the posterior over valid solutions and making the final outcome more stable.

Reinforcement learning discovers this automatically. When reward is sparse and correctness matters, short trajectories exhibit high variance and low expected return. Longer trajectories allow incremental conditioning, partial verification, and error correction, which lowers variance even if bias increases slightly. Gradient descent selects for this regime without any notion of “thinking.”

So the effectiveness of step-by-step reasoning is not psychological and not accidental. It is an expression of a general principle: for sufficiently complex problems, stability requires spending time to buy structure. Humans and models converge on the same strategy because both are optimizing under the same computational constraints.

Thinking models and the RLVR inflection point

Late last year, OpenAI’s o1 introduced the first production-scale “reasoning model” — one that baked an agentic reasoning loop directly into inference. Shortly after, DeepSeek-R1 demonstrated that this capability was not proprietary magic but an emergent consequence of reinforcement learning with verifiable rewards.

The results were immediate and striking. Compared to GPT-4o, o1-preview jumped 43 percentage points on AIME 2024 and 22 points on GPQA Diamond, while moving from the 11th to the 62nd percentile on Codeforces. Nothing about the base architecture fundamentally changed. What changed was the model’s incentive structure.

This is the key lesson of 2025:

Reasoning didn’t improve because models learned logic.

It emerged because gradient descent finally had an outcome to optimize toward.

Reasoning as trajectory optimization

To see why this works, it helps to stop thinking in terms of tokens and start thinking in terms of trajectories.

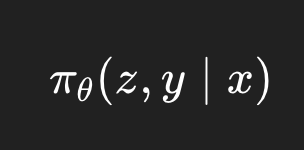

A thinking model defines a policy

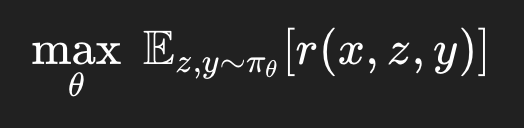

over an internal trace z and a final answer y. During reinforcement learning, we optimize:

where r is a verifiable reward: correct math, passing tests, valid proofs.

The policy gradient doesn’t know or care what “reasoning” is. It simply increases the probability of trajectories that lead to reward. If longer traces correlate with correctness, the model learns to generate longer traces. If verification steps correlate with success, verification emerges. No one has to tell the model to think harder. The optimizer does that automatically.

This is why reasoning length increased monotonically during RL training in DeepSeek-R1, even though length was never explicitly rewarded.

Why “thinking” feels real

From the outside, these models look more rational. They explain their answers. They double-check themselves. They appear deliberate.

But this is where 2025 research injects a necessary dose of skepticism.

Apple showed that reasoning models fail catastrophically on puzzles that exceed a certain complexity threshold, even when provided with explicit algorithms. Anthropic demonstrated that reasoning traces can be post-hoc rationalizations, omitting crucial cues that actually determined the output. In other words, the model may have used a hint — but its explanation pretends it didn’t.

This reveals something important: thinking models are not executing symbolic algorithms. They are performing reward-shaped search in a latent space that happens to look like reasoning when rendered as text.

Compute is the new reasoning primitive

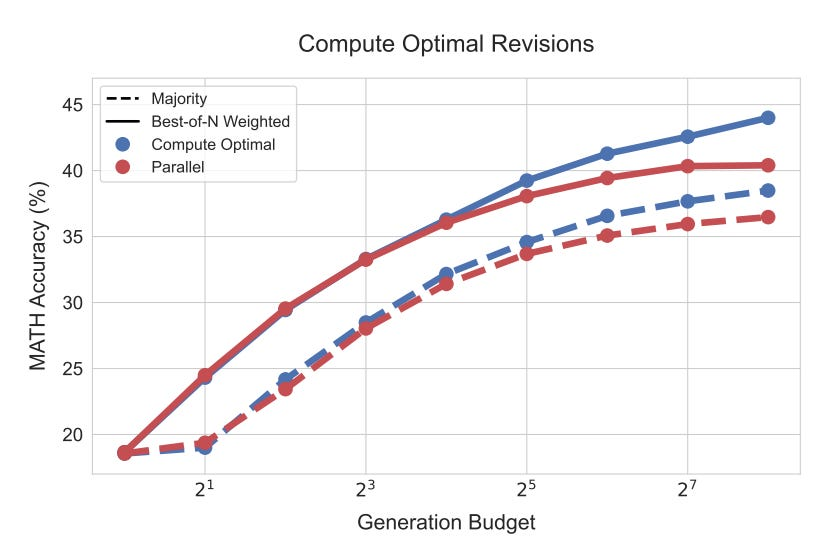

One of the most underappreciated changes in 2025 is that test-time compute became a first-class knob.

Gemini 3 Flash with reasoning enabled used 160 million tokens to run Artificial Analysis’ Intelligence Index, achieving a score of 71. Without reasoning, it used only 7.4 million tokens and scored 55. Claude Opus 4.5 and GPT-5.1 both reach the same score, but one uses nearly half the tokens of the other.

Reasoning works — but it’s expensive.

This reframes reasoning as an economic problem. You are no longer asking “Can the model reason?” but “How much thinking can I afford?”

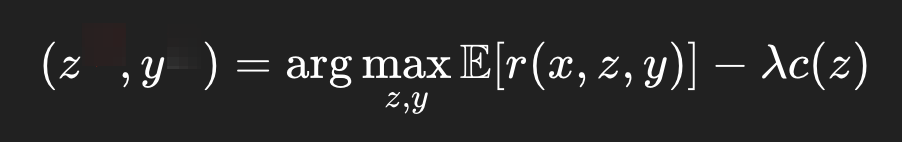

Formally, inference becomes:

where c(z) is token cost, tool usage, or latency. This equation quietly governs every modern thinking model.

[ref]

Tools and agents

Once reasoning is treated as a trajectory rather than a monologue, it naturally extends beyond language.

Reasoning models perform even better when they can call tools. OpenAI o4-mini gained over 3 percentage points on a 100-domain multimodal benchmark simply by using tools. Robotics models like ThinkAct saw ~8% gains when rewarded for reaching goals rather than predicting actions. Agents like AlphaEvolve and AI Co-Scientist use Gemini to generate, evaluate, and iteratively improve code or scientific hypotheses, closing loops that resemble scientific reasoning more than text generation.

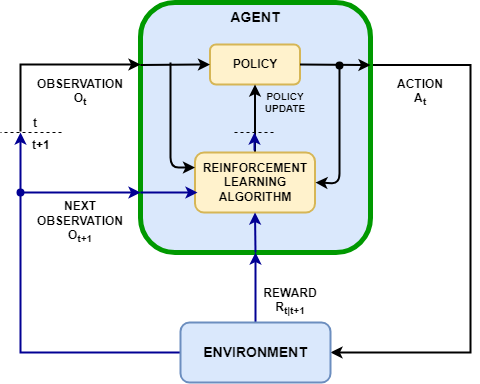

In these systems, reasoning is no longer a chain of thought. It is a control loop: propose → test → revise.

Why reasoning breaks in the real world

Despite all this progress, reasoning still fails in places that matter.

The reason is simple: most real problems are not verifiable. Rewards are delayed, noisy, or subjective. In these settings, RLVR collapses into shortcut-seeking.

This is why SWE-bench keeps evolving, why agents fail silently, and why retries sometimes outperform “thinking harder.” The loop matters more than the explanation.

The hidden bottleneck: memory

By the end of 2025, a deeper limitation became impossible to ignore. Reasoning is inherently temporal, but models forget.

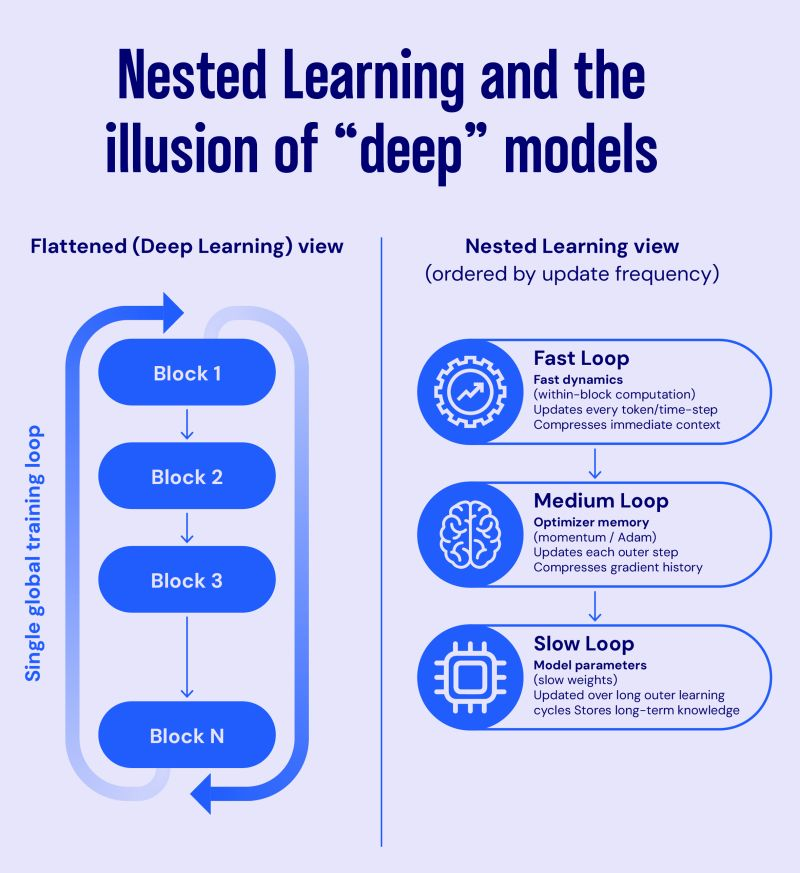

They reason brilliantly within a context window, then reset. Agents solve tasks, then fail to accumulate abstractions. This is why continual learning re-entered the conversation. Google’s Nested Learning work is important not because it solves memory, but because it formalizes the tension between fast adaptation and slow consolidation.

Reasoning without memory is short-horizon optimization.

What thinking models really are

In 2025, reasoning lives in the objective, the verifier, the inference loop, the compute budget, the toolchain, and the memory system. Models don’t have reasoning. They are allowed to buy it.

Traces are also programs

A useful mental shift is this:

A reasoning trace is not an explanation.

It is the serialized execution of a latent program.

Consider a simple symbolic algorithm: computing the sum of the first n integers.

Symbolic version:

def sum_n(n):

total = 0

for i in range(1, n+1):

total += i

return total

A reasoning LLM trace for n=5 might look like:

We want the sum from 1 to 5. Start with 1 + 2 = 3. Add 3 gives 6. Add 4 gives 10. Add 5 gives 15. So the answer is 15.

These look different, but computationally they are doing the same thing:

- maintaining state (

total) - updating it incrementally

- converging to a final value

The difference is where the state lives. In symbolic systems, it lives in memory. In LLMs, it lives in tokens and attention.

What traces look like in modern reasoning models

By 2025, traces stopped being simple chains. Real reasoning traces often include:

- Decomposition

- Let’s break the problem into parts:

(1) understand constraints

(2) derive formula

(3) verify edge cases

- Let’s break the problem into parts:

- Branching

- Option A: assume X is increasing.

- Option B: assume X is constant.

- Let’s test Option A first.

- Verification

- Check the result against a small example.

If n = 1, formula gives 1. Correct.

- Check the result against a small example.

- Tool calls

- Run a quick calculation in Python to confirm.

- Backtracking

- That assumption leads to a contradiction.

Let’s revisit step (2).

- That assumption leads to a contradiction.

These are not stylistic flourishes. They are control flow constructs, expressed in natural language.

Teaching models to reason: SFT sets syntax, RFT selects semantics

The SFT vs RFT debate sounds philosophical, but in practice it’s very mechanical.

Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT)

SFT is how you teach the model what a trace should look like.

For example, you might enforce a schema:

THOUGHT: SUBPROBLEM: SOLUTION: VERIFY: ANSWER:

An SFT example might look like:

{

"input": "Solve the equation x^2 - 5x + 6 = 0",

"output": "THOUGHT: Factor the quadratic.\nSUBPROBLEM: Find two numbers that multiply to 6 and sum to -5.\nSOLUTION: (-2, -3).\nVERIFY: (-2)*(-3)=6, sum=-5.\nANSWER: x=2,3"

}

This doesn’t make the model correct. It makes it structured.

Reinforcement Fine-Tuning (RFT / RLVR): teach what works

Now you add a verifier. For math, it might be simple:

def verifier(problem, model_answer):

try:

return int(check_answer(problem, model_answer))

except:

return 0

And run RL loop:

for episode in range(N):

trace, answer = model.sample(problem)

reward = verifier(problem, answer)

model.update(trace, reward)

What happens is subtle but powerful:

- traces that look good but fail verification lose probability mass

- traces that succeed get amplified

- the model learns when longer deliberation is worth it

This is where “thinking before speaking” emerges.

* We will cover actual RL algorithms PPO / GRPO in a another post.